FEBRUARY 2025

Editorial

Dear Friends,

When I first came to Sackville in 1969, I recall seeing all the small barns on the so-named “Tantramar Marshes” and wondering why so many barns were present and no cattle (nor marsh!) of any kind were apparent anywhere. Well, here I am, fifty-six years later, able unequivocally to solve that conundrum. Soon after my initial arrival to this community, I started asking around about this and was told that those small barns were used primarily to store hay. This was at a time when horses, fueled by hay, ruled the roads. Beyond this, I never fully appreciated the history and background of the hay business in Sackville. But now I am pleased to inform you that, through this newsletter, we can describe the “legacy” of hay production in the Tantramar region and also, through the efforts of Kathy Trueman, quantify this activity that so benefitted our region.

Also, when I first came to Sackville, Alex Colville was a citizen of this town and taught at Mount Allison University. Mark Holton, who in an earlier issue of this newsletter regaled us with stories of early currencies, in this issue tells us about Colville’s 1967 designs on our coinage. After you read Mark’s story, check the coins you are carrying in your wallets and admire the designs depicted on them. You may no longer take them for granted.

Much of the population of the Maritime region live close to the ocean, a consequence of which is that our history is peppered with sea captains’ sailing stories. In this issue of the newsletter, Captain C.C. Dixon, originally from Sackville, recorded half a century of sailing the ocean waters through a book published in 1933, now in the Tantramar Heritage Trust’s library and reviewed herein by Jeff Ward. It is a harrowing tale so put on your seat belts!

To complete this issue of your newsletter, Colin MacKinnon introduces us to boot and shoe maker Edmund Kaye of Wilbur’s Cove, Rockport, NB, who practiced his craft in the late 1860s and early 1870s. It is a pleasure to welcome Edmund and his family to our heritage community and also express our gratitude to Colin for this most interesting introduction to the Kaye family.

We hope that the articles in this newsletter help you to develop a deeper appreciation for our marsh barns, currency, marine history and shoe making.

Enjoy!

— Peter Hicklin

Maritime Hay Producing Legacy

by Katherine Trueman

Haying on the Tantramar Marshes by Ruth Miller Henderson (1903-1987). Photo by Al Smith.

The following article appeared on May 28, 2003, in the Sackville Tribune-Post under the title Tantramar’s Rich Legacy of Hay Production and, that same month and year, in the newsletter of the Canadian Hay Association. It remains meaningful today as a significant part of Tantramar history. – Editor

The early hay industry in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia centers in large part around the tidal rivers of the Bay of Fundy, particularly in Chignecto Bay and the Minas Basin at its head. Acadian settlers first began using their land-reclaiming technology in the mid-17th century by dyking along small tidal rivers to develop agricultural land. Later settlers arriving in the latter half of the 18th century maintained and expanded this system of dykes and aboideaus and used the hay produced to supply a burgeoning export market that continued to grow throughout the latter half of the 19th century through to the 1920s. These dykelands included the Annapolis River area, the Memramcook Marsh, the Shepody/Petitcodiac areas in Albert County, the area in and around Minudie and the celebrated Tantramar Marsh near Sackville, New Brunswick.

Timothy hay from these areas was shipped along the eastern seaboard to feed the growing cities of New York and Boston, locally to the rapidly expanding city of Halifax, and further afield to Newfoundland where hay would have been in short supply. Hay shipments were also critical to supplying feed for the horses and ponies that worked in coal mines and logging operations. Early producers estimate that at least 100 tons a month went to Cape Breton for the horses and ponies working in those coal mines.1

While it is difficult to obtain exact figures for the number of acres of marsh or dykeland under cultivation, it is possible to get an approximation. The Handbook of the Dominion of Canada prepared by the Congress of Chambers of Commerce in 1903 reports on New Brunswick that: “There are considerable stretches of dyked land in the province on which large crops of hay are grown. The agricultural returns [which do not differentiate between “dykeland” and “upland”] show about one million acres under cultivation, about half of which is hay.”2 In 1907, Howard Trueman estimated in Early Agriculture in the Atlantic Provinces that in the Tantramar area “there are about 50,000 acres of marsh [dykeland]”.3 For an indication of production, the Canada Year Book 1905 shows that between 1871 and 1901 hay production in New Brunswick increased from 345,000 to 512,000 tons.4 A large portion of this productio5 would have been exported.

The high tides of the Bay of Fundy deposit fine nutrient-rich sediment along the tidal rivers. A layer of sediment 2-3 centimetres thick may be left following a single tide and, in some places, the accumulated depth of sediment, over time, reached more than 40 metres.5 Tides kept the tidal lands fertile and lush and the strength of the outgoing tides drained the marshes and provided an opportunity for salt grasses to take root in the deep red mud.6

The Acadians saw the potential of the extensive salt marshes and began to dyke them using aboideaus, hinged sluices that allow fresh water to drain off at low tide and close to keep out sea water at high tide. After dyking, the marshes were freed from salt by rainwater. Later settlers expanded the system of aboideaus and developed new ways of both re-silting and draining freshwater off the dykelands. These included the system of canals developed and used by the engineer Tolar Thompson in the early 19th century. Aboideaus still form the basis of the dyke system used today.

An aboideau (or sluice) is essentially a long rectangular box, originally made of hollowed logs and later of timber, with a hinged gate. The dimensions of an aboideau can vary with the volume of water it is expected to handle but they can be quite substantial in size measuring, for example, 16 m long, 5 m wide and 2 m deep. Construction of a dyke and aboideau could take several years and was often fraught with obstacles and frustrations. The positioning and anchoring of the aboideau was particularly critical. The aboideau would be located in a creek bed at low tide during a period of neap tides and then anchored into position with marsh clay and fine brush. Speed was essential to complete the task before the tide turned and carried the aboideau out to sea. In one case in 1804, a group of men working on the Aulac River in the Tantramar area did not succeed. The rush of the incoming tide dislodged the aboideau. Four of the men (all from the same family) jumped aboard to save the aboideau but were carried out along the river towards the Cumberland Basin and Chignecto Bay. They spent the night hanging onto the aboideau waiting for the currents to carry them close to shore. The following morning they grounded in Nappan (20 km down the Basin), sent word home of their safety and enjoyed the hospitality offered from those at a nearby farm house and later re-boarded the aboideau to ride the tide back up the Basin.7

The soil of the dykelands is characterized by a high nutrient content and many early accounts report that rich crops of hay were produced year after year without use of any fertilizers or manure. From well drained dykelands, producers could expect to obtain no less than two tons to the acre and, in some cases, upwards of three tons of fine, high quality timothy hay. Dykeland hay retains its green colour and retains its palatability longer than upland or high ground hay and this has always been an attractive selling feature of the product. If early settlers felt the need to reinvigorate the soil they would completely flood the land for a period and then go through the process of desalination. Dykeland was highly valued and continued to sell for higher prices than upland for many years. Prices peaked between 1890 and 1920 at $150-$200 per acre.8

Demand for hay grew rapidly between 1850 and 1920 as local mining and lumber operations prospered and cities expanded. One reason the export trade developed in the very early years along the dykelands was the relatively easy access to port facilities where hay would be loaded onto schooners. While few today recall this schooner trade, stories are retold. One early producer loaded hay at the Port of Sackville and traveled with the schooner to St. Martins, NB, a two-day trip. Because of a storm the two-day journey took less than one night.9

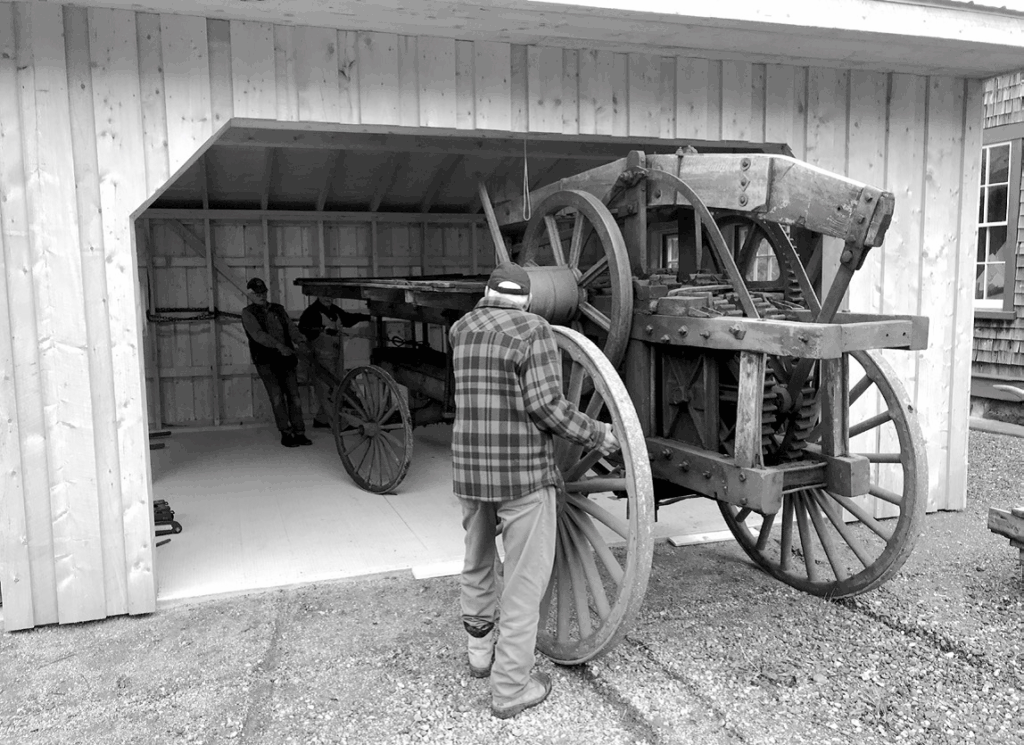

Photo of a c1890s era hay press being operated at Doncaster Farm Antique Farm Show during Sackville’s Fall Fair Weekend, August 2004. Photo by Jim Wheaton

The antique hay press shown above was donated to the Tantramar Heritage Trust by Roy Dixon in 2023. This photo by Paul Bogaard shows it being placed in the Carriage Shed at the Campbell Carriage Factory Museum by Al Smith and Bill Snowdon.

Critical to supplying the increased demand for hay was the introduction of the first hay presses (see accompanying photos) which allowed producers to package their product in easy to handle 100-150 lb bales tied with either 2 or 3 strands of wire. One producer recalls discussions about earlier methods used to package hay where hemlock saplings in a wooden frame were used; as much hay as possible was pressed into the frame and then the saplings were tied together to make a bale.10 Hay presses revolutionized this process even though, by today’s standards, these presses appear cumbersome. Common practice in the Tantramar area was to store hay loose in marsh barns during the summer and fall. In winter, teams of 5-6 men traveled from marsh barn to marsh barn throughout the area pressing hay. The press was hauled to the barns by a team of horses, sometimes requiring more than one team in heavy snows. Horses powered the early presses but as soon as gasoline engines became available they became the preferred source of power and also had to be hauled to the site using horses. The average press was operated by a seven-horsepower engine. An experienced team set up the press with the engine and began their work. Pressed hay was then moved to the closest rail siding (by bobsled and later truck) and loaded onto a boxcar.11 The team of 6 men worked as follows: one man to feed the press, one to tie the bales, one to weigh the bales and 2-3 to work in the mow moving the loose hay. If the mow had been well stacked it could be done with two men but the task required three if this work had not been done expertly.

The average marsh barn held 40 tons of loose hay and the average box car 18 tons of pressed bales.12 An experienced team could press between 370 and 400 bales a day.13 Often, but not always, a small caboose was hauled to the site along with the press and engine. The caboose had a small wood stove and provided a warm place for the men to rest, eat their lunch or wait for repairs. The price paid for pressing hay ranged from $1.00 to $1.75 per ton.14 Hay was moved from the barn to the rail siding and loaded into the boxcar for $.50 per ton.15 It is estimated that between 25,000 to 30,000 tons of hay per year were harvested and sold from the Tantramar dykelands during the peak years. This is in addition to the hay required locally for livestock.

Sometimes the same teams that pressed hay in winter were contracted to cut and stow hay in the marsh barns during summer. However, there were also people who specialized in the mowing and stowing of hay. One young couple, newly married, started such a business and operated for several years during the 1940s. They moved for the summer into rented accommodations away from their home place and close to the hay land. They employed five hired men and operated a one-horse rake machine, a five-foot mower, and several wooden wheeled carts along with the required teams of horses (usually two). The hay was mowed, raked and cured. It was then forked onto the wagons and moved to the barns where it was unloaded into the bays using a pitch machine. The horse that operated the rake was also used on the pitch machine. Eventually a hay loader was added to their business and the young wife managed the team for the loader (with two babies in a special box on the front). Hay in the bays was measured to calculate tonnage.

They managed to harvest and stow approximately 250 to 300 tons a season and received between $3.50 to $4.50 per ton. Hired men were paid around $.75 per day.16

A distinguishing feature of the Tantramar Marsh landscape was the large number of gray, weathered marsh barns that proliferated as part of the early hay industry. Most barns were 30′ x 40′ with a 15′ foot post. They were constructed on a set of blocks and the floors of the bays were poles set on stringers. This acted as a dryer when air flowing beneath the sills of the barn was drawn up through the mows of hay. Several hundred barns once covered the dykelands; most farms had at least one or two, many had between three and five, and some had as many as seven or eight.17 Today, only a small number of these barns remain.

The hay presses operated until as late as the early 1950s when field balers became available.18 The large number of presses in the area, even in later years, is notable. However, demand for hay changed dramatically by the end of the 1920s with the introduction of gasoline engines that replaced horsepower (although horses continued to be used in the woods until as late as the 1950s). By 1938, the price of hay had dropped as low as $4.00 per ton resulting in a corresponding decrease in the value of dykeland.19

The middle of the twentieth century marked the decline of what had been the golden age of the Maritime hay industry. However, this was not the end of the story but a turning point in the production and marketing of a local commodity. Today, dykes and aboideaus in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia protect 82,000 acres of tidal land.20 Timothy hay continues to be exported from the Maritimes to international markets in double compressed bales, small bales (50-60 lbs) and mid-sized bales (800 lbs).

Endnotes

1 Alice Trueman, “Point de Bute – A Reconstruction”. The reference comes from an interview she conducted with Raymond Trueman on January 27, 1973.

2 Congress of the Chambers of Commerce of the Empire, Handbook of the Dominion of Canada, pp.35.

3 Howard T. Trueman, Early Agriculture in the Atlantic Provinces, The Times Printing Company, Moncton, NB, 1907. pp 95.

4 Canada Year Book 1905, pp 79.

5 Maritime Dykelands, pp 1 and 7.

6 There is a distinction to be made between salt grasses (Spartina) and tame (or English) grasses (principally timothy and clover). The salt grasses were harvested as broadleaf hay from uncultivated dykelands in late September and early October. This hay was used locally until the 1970s. Timothy hay was harvested in mid-summer and used primarily for export.

7 Howard T. Trueman, The Chignecto Isthmus, pp 103-104.

8 Price depended on location and drainage and various prices are quoted. Howard T. Truman writes in 1907: “Marsh situated near the towns and well placed for drainage is worth upwards of $180 to $200 per acre,” pp 100. See also Maritime Dykelands The 350 Year Struggle, pp 3.

9 This occurred to local producer William A. Trueman sometime between 1897 and 1905.

10 Interview with Mr. Charles Anderson, January 28, 2003.

11 The introduction of the railway transformed the transportation of hay for export.

12 The smaller boxcars would hold approximately 12 tons of hay.

13 Interview with Mr. Charles Anderson, January 28, 2003.

14 Alice Trueman, Point de Bute, pp 15. One local producer recalls paying $1.20 per ton for pressing hay. Interview with Mr. Howard G. Trueman, February 8, 2003.

15 Interview with Mr. John Carter, February 5, 2003.

16 Interview with Mrs. Olive Allen and Mr. Walter Trenholm, February 23, 2003. Mrs. Olive Allen with her husband Mr. Ronald Allen, operated this business from approximately 1942 to 1948. Mrs. Allen was responsible for preparing meals for the hired men. They worked mainly with Mr. Albert Wheaton and also Ms. Willy Wood.

17 Interview with Mr. George Trueman, February 7, 2003.

18 Prospect Farm loaded the last marsh barn with loose hay in 1952. A field baler was purchased in 1953.

19 Many sources quote $6.00 per ton including Maritime Dykelands, pp 4. However, Mr. Aubrey Trenholm, local producer, recalls his father selling hay for $4.00 per ton in the 1930s.

Mr. Howard G. Trueman, local producer, also recalls selling

hay for $4.00 per ton.

20 Maritime Dykelands, pp 5.

References

Articles & Papers

A Century Gone By, Sackville Tribune Post, January 5, 2000.

Sackville Celebrated ‘Hayday’ in the Late 1800s, Early 1900s. Sackville Tribune Post, June 19, 2002.

The Port of Sackville, Sackville Tribune Post, October 9, 1996.

Trueman, Alice. Point de Bute – A Reconstruction, 1973.

Interviews

Ms. Olive Allen and Mr. Walter Trenholm, February 23, 2003.

Mr. John Carter, retired producer and equipment dealer, February 5, 2003.

Mr. Charles Anderson, local producer (worked as a member of a press team for five years), January 28, 2003.

Mr. Michael Green, Marshland Engineering Technologist, New Brunswick Department Agriculture, Fisheries and Aquaculture, January 28, 2003.

Mr. James Sloan, retired hay marketer, January 28, 2003.

Mr. George Trueman, Manager, Ridgeway Forage and Grain, January 29 and February 7, 2003.

Mr. Howard G. Trueman, retired producer, February 8, 2003.

Books and Government Publications

Annual Report of the Department of Agriculture of the Province of New Brunswick, 1940.

Bowser, Elaine et al. A Profile of the Tantramar Marshes, Sackville, NB, 1978.

Canada Year Book 1905. 2nd Series, Kings Printer, 1906.

Handbook of Dominion of Canada. Congress of Chambers of Commerce of the Empire, 1903.

Maritime Dykelands The 350 Year Struggle. Department of Government Services, Province of Nova Scotia, 1987.

Monroe, Alex. History, Geography & Statistics of British North America. John Lovell, St. Nicholas Street, Montreal, 1864.

Sears, W.W. and MacKay, D. This is Sackville. Tribune Press, 1968.

Sixty Years of Canadian Progress 1867-1927. National Committee for the Celebration of the Diamond Jubilee of Confederation, 1927.

Trueman, Howard T. Early Agriculture in the Atlantic Provinces. The Times Printing Company, Moncton, 1907.

Trueman, Howard T. The Chignecto Isthmus and Its First Settlers. William Briggs, Toronto, 1902.

Webster, J. Clarence. An Historical Guide to New Brunswick. New Brunswick Government Bureau of Information and Tourist Travel, 1947.

A Million Miles in Sail – A Commentary

The Tantramar Heritage Trust is in the process of receiving a new literary treasure for its library, the result of a book exchange between two valued members of the Trust: Al Smith and Jeff Ward. Here, Jeff presents us with an interesting review of the book which, later this month, should become part of the Tantramar Heritage Trusts’ library. There is an interesting story associated with this “exchange” which I felt should be noted for our readership as I consider it very interesting and relevant.

Recently, Al informed Jeff about our most recent book Fifty Years a Sailor, the memoirs of Sackville sea captain Stephen Barnes Atkinson. Jeff replied that he also had a book about sailing adventures entitled A Million Miles in Sail by John H. McCullough. (Please note that Jeff later informed me that the full title is A Million Miles in Sail, Being the Story of the Sea Career of Captain C.C. Dixon but, for the sake of brevity, I’ll stick with the short form.) They agreed to a book exchange: a copy of Stephen Atkinson’s memoirs to Jeff for a copy of Capt. Charles Dixon’s adventures to Al. Later this month, the Dixon book will be accessioned for the Trusts’ Research Centre. Al did some genealogical research and here is what he submitted:

“Capt. C.C. Dixon was the grandson of Sackville shipbuilder Charles Dixon and his wife Sarah Boultenhouse. A Million Miles in Sail was professionally written by English journalist Joshua H. McCullough, who writes the story in Capt. Dixon’s voice. The book was published in Britain in 1933. Ray Dixon had a copy of the book given to him by an aunt many years ago. I borrowed the book from Ray and read it over the Christmas break. It covers snippets of Dixon’s adventures on tall ships from 1881 to 1919. Commencing at a time when he was just 10 years old, he went to sea with his father Capt. Robert Y. Dixon. He eventually worked his way up to Captain and was the Master of two British barques: Arctic Storm and Elginshire. The book is a wonderful read and in addition to relating thrilling and dangerous episodes of his years at sea, he was a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. His stories often relate to his exploring of remote islands in the South Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans.”

This note from Al Smith was received by email on January 4, 2025.—Peter Hicklin

A Million Miles at Sea – A Belated Review

by Jeff Ward

A Million Miles in Sail is the memoir of Captain C.C. Dixon, a Boultenhouse descendent. The book was published in 1933 when the days of sail-powered transport had largely passed. Dixon’s memoir is one of a great many books published in the interwar period when it seems many old seadogs found a nee —and a market—to tell their stories to an eager audience.

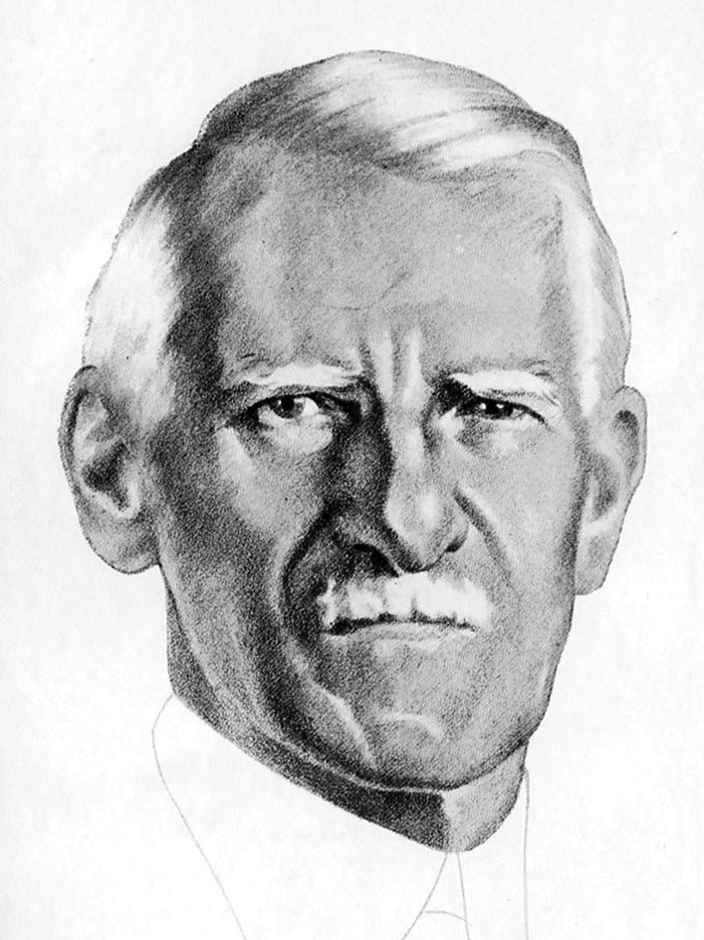

Captain Charles C. Dixon (1873-1947).

Charles Chubbuck Dixon (1873-1947) was born in Nova Scotia to Robert Young Dixon and Hanna Augusta Chubbuck. He was their only surviving child, two siblings having died young. His parents were cousins, grandchildren of Edward Dixon of Sackville. Hanna’s father, James Chubbuck was a shipbuilder in Parrsboro; Hannah often sailed with her husband on his voyages, and Charles as well. Robert’s parents were Charles Dixon and Sarah Boultenhouse. As Al Smith notes in “What’s in a Name?” (The White Fence #100), Sackville’s Charles Street is named for the elder Charles Dixon. C.C. Dixon began life as a sailor, first as a deck boy of 10, and eventually worked his way up to captain.

One of the impressions that stayed me after reading the book is the constant sound of the wind. It is a windy book, and in a nice way. It’s a wonderful read, but it no doubt benefits by having been written by a professional writer, the English journalist John Herries McCulloch who writes in Dixon’s voice.

Herries does an excellent job of conveying a sense of the sea. He writes about one of Dixon’s first memories: “The most vivid recollection I have of my childhood days had a stormy setting on the ocean. It carries me back to the year 1881. I was in the S. Vaughn, a 900-ton barque that my father was taking from Liverpool to Valparaiso, Chile. We had worked out into the Irish Channel when dirty weather overtook us. It began, I remember, with a heavy wind from the south-east. In the Irish Channel this inevitably spelled trouble for windjammers…”. The vessel was pushed towards the shore, which would threaten her breaking up, so his father dropped a weather anchor. This kept the vessel off shore but the severe weather continued to pound so badly that the weather cable snapped and he was eventually forced to order that the masts be brought down: “Tide-rode as our ship was, the wind held the masts while the lee rigging was cut. This left them supported by weather rigging only; that was cut, and the main and foremast went safely by the board.” His father jury rigged a longer anchor cable and was finally able to control the vessel.

But without sails he had no power. All he could do now was seek assistance. “I remember how excited I was when Father came down to the cabin, after the cable had been lengthened, and wrote a message on a piece of paper. A pretty desperate message it was. The paper was placed in a cask, and the cask was rigged with a weight in one end and a flag on the other.” Remarkably, the cask was found the next day on the Irish coast and eventually the vessel was brought to safety.

In 1883 he was with his father on a voyage from Saint John to Manila aboard the Marabout of Saint John. They just missed the eruption of Krakatau in the Sunda Strait between the Indian Ocean and the Java Sea: “I shall never forget it, for we missed its vortex by a narrow margin, and I still carry clearly in my mind the dreadful scene of its aftermath—the frightening darkness, the sea of pumice-stone, the empty sea where the island should have been, and the altered straits through which my father had to pick his way.”

The book is filled with thrilling episodes like these. These sample chapter titles give a sense of this: Shanghaied in Rio, The Stormy Atlantic, Round the Horn, and The Sinister Sargasso. In one chapter, Forgotten Islands, he writes about obscure islands he visited during his epic career. Here’s a quote from the book about his experience when he took a calculated risk to visit Amsterdam Island, a thousand miles southwest of Tasmania: “It has tens of thousands of ocean all to itself. … Our sailing directions told us that there were some wild cattle on Amsterdam, and there they were, a whole herd of them. … They were a sight for the hungry eyes of sailors who had been chewing salt meat for months, and I decided there and then to try for one of the animals.” The sea was calm and the winds were low, so Dixon decided to let his ship, the Elginshire, drift as he and members of the crew rowed ashore. After a comical and yet terrifying encounter with a bull, he succeeded in shooting an animal and got back onto the rowboat with a load of fresh meat.

But they had lost time. “After noon had passed into evening, a wind had sprung up and the ship was nowhere in sight. We sped away to the eastward. An hour passed and no sign of the ship. Darkness fell. … it was quite dark now and I was steering by the compass. It began to look as if we might have to make our way to Australia in the lifeboat.” They decided to light flares, without success, and after exhausting their supply, they resorted to starting a fire. “A moment later we saw an answering flare. Were we relieved? …We didn’t get back too soon, for before midnight a gale was howling and heavy seas were sweeping the decks.” Thrilling stuff.

1967 and the Coins of Alex Colville

by Mark Holton

One cent, silver dollar, and five cent (nickel) pieces showing the Colville designs. Photo by Al Smith.

“I think in a sense the things I show are moments in which everything seems perfect and something is revealed.”1 So said Alex Colville, artist, teacher, painter, and printmaker who designed our 1967 coins.

The year 1967 was a very special year for Canada. It was Centennial Year, a year of celebration, of special events large and small and a year of tremendous optimism. Expo ’67, an international world’s fair, attracted millions to Montreal from around the world. Organized by Canadians, Expo was a huge success and did much to make us feel good about ourselves.

In addition to Expo, other noteworthy events took place elsewhere across Canada. The Order of Canada was inaugurated, Toronto won the Stanley Cup, and parks, museums, art galleries, libraries and other special cultural facilities were constructed, opened, expanded, re-dedicated and celebrated. No one noticed that we didn’t have computers, smart phones, flat-screen TVs, SUVs, push-button dialing, Wikipedia, fax machines, e-mail, laptops, robocalls, “fake news” and “apps” for everything from restaurant reservations to taxis. No one seemed to mind the rotary dial on their telephone or that most television programmes were still in black-and-white. The Polaroid instant camera was very popular while poutine and donairs were virtually unknown.

In 1967 our coins were still made of real silver2, our paper money was made of paper and few people carried “plastic.” Debit cards were unknown, likewise ATMs and online banking. Banks opened promptly at 10 am, closed precisely at 3 (except some stayed open as late as 6 pm on Friday) and gave us the expression, occasionally used pejoratively, “bankers’ hours”. Most of the leading people in public life were male, favoured dark suits, and, like Governor-General Georges Vanier, Prime Minister Lester Pearson, and opposition leader John Diefenbaker, were veterans of The Great War.

Ideas large and small were brought forward for celebrating our one hundredth anniversary. One idea was a special set of coins. Coins are seen and handled by everyone. They can be magnificent pieces of propaganda, and boosters of national pride and identity. If Canada’s Centennial was to be more widely celebrated then special designs on coins would be an excellent way to reach all Canadians. In 1964, the Minister of Finance announced a competition to select appropriate designs. A committee was established and after deliberation, selected in 1966 the designs of Alex Colville (1920-2013), an artist living in Sackville, New Brunswick, for the reverse of Canada’s coins. Colville’s designs featured not people, places or things but three animals—two birds and a fish.

“I think of animals as being incapable of evil and I certainly don’t think this about people. The idea of a bad dog is absolutely inconceivable to me, unless it has been driven crazy by people.”

After graduating with his Fine Arts degree from Mount Allison University, Colville joined the army. In his mid-20s, as a Canadian war artist in northwest Europe, Colville saw and documented the horrors of both the battlefield and the concentration camp. In April 1945, he spent several days making drawings at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. The chaos of war had a powerful effect on him as it did on the lives of all soldiers. Colville’s painting career would be marked by a desire for order and a distaste for what was irrational and evil. Animals, incapable of evil, would appear often in his art.

For his set of coins, Colville stated he “wished to use creatures which were common, which had certain moving or symbolic associations, and which had not been made trite by repeated and, perhaps, unthinking usage.” Like many of his paintings, Colville’s designs could be open to several interpretations. On the largest coin, the silver dollar, he presented the Canada goose in flight, “one of our most majestic creatures and also particularly Canadian”. With associations of “travelling over great spaces”, Colville admired the “serene dynamic quality” of the goose. The second-largest coin was the silver fifty cent coin and it bore the image of a wolf, “symbolic of the vastness and loneliness of Canada, and thus of our tradition and, to a degree, of our present condition. Yet the wolf is not a pathetic creature.” Representative of Canada, these animals also show a certain detachment.

These coins were struck in considerable number, over 6 million dollars and over 4 million half-dollars, but these coins were not as widely seen as the four most common coins. The twenty-five cent coin (the bobcat, 50 million made), the ten-cent coin (the mackerel, 60 million), the five-cent coin (the rabbit, over 35 million) and the one-cent coin (the rock dove, almost 350 million) were struck in quantity and even today, almost 50 years later, the occasional Colville coin is found in one’s change.

Each creature appealed to Colville for specific reasons. He selected the bobcat for the quarter because it is “expressive of a certain intelligent independence and capacity for formidable action.” The dime presented a special problem due to its small size, but the mackerel was “a simple and unambiguous image. … one of the most beautiful and streamlined fish, common on both coasts. The fish has ancient religious implications; I think of it as a symbol of continuity.”

The rabbit (a.k.a. Varying Hare, Snowshoe Hare or Snowshoe Rabbit) appears on the nickel. In the press release announcing the selection of Colville’s designs the artist remarked that the rabbit is “much loved by children, perhaps because of its vulnerability. It survives by alertness and speed, and is symbolically connected with ideas of fertility, new life and promise—it is thus a future-oriented animal.”

Finally, the cent. This was the first alteration in the design of the cent since 1937. This was also true for the dime and quarter. According to Colville, “…I wished to use a very common bird, but one with symbolic overtones. I selected the dove (rock dove)—very common, in cities as well as the country, as the pigeon, and having associations with spiritual values and also with peace.”3

Peace, comfort and order are what Colville found in animals, and the absence of evil. Also absent, but provided by the viewer, is the context or environment of each creature. Unlike the beaver on the regular five-cent coin, firmly rooted to his rock and surrounded by the safety of water, Colville’s creatures are suspended in space and in our imagination. The viewer is invited to complete the design with their own experience and knowledge, making the animal less alien, less the floating stranger. In his artistic career, from his student days at Mount Allison University in the early 1940s to his final years in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, art historian David Burnett estimates that one third of Colville’s paintings and half of his serigraphs “have animals either as their main subject or as a significant part of the image.”4 Burnett points out that by depicting animals, “Colville shows us an aspect of communication, an example of something united with its surrounding. By contrast they point to how we are frequently disoriented, uncertain and anxious.”5

Colville goes further. In a publication prepared for an exhibition with the Mira Godard Gallery in Toronto in March, 1987, Colville noted that “I see life as inherently dangerous. I have what is essentially a dark view of the world and human affairs. Living in the midst of hazards, I don’t see how any reasonably intelligent and experienced person can not feel anxiety. Anxiety is normality in our age.”

For what on the surface is simply the design of six coins, this is heavy baggage indeed. But we have the choice: admire them for what they are, images of well-known Canadian animals, fish and birds, or view them as something else, objects to be contemplated for what they tell us about ourselves and the world we live in. As Colville might say, his centennial creatures are indeed perfect, and revealed.

Endnotes

1 Quoted by John DeMont in “Alex Colville’s terrible beauty”, Maclean’s magazine, October 10, 1994, page 61.

2 Part way through 1967 the price of silver increased considerably and the Mint reduced the silver content of 1967 dimes and quarters from .800 to .500 silver. Silver in our coins disappeared in 1968.

3 J. R. C. Perkin, Ordinary Magic; a Biographical Sketch of Alex Colville, with reproductions of his more recent works. Hantsport, Nova Scotia: Lancelot Press Limited, 1995, page 72-73.

4 David Burnett, Colville. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario and McClelland and Stewart, 1983, page 157.

5 Burnett, page 178.

Edmund Kaye, Boot and Shoemaker of Wilbur’s Cove

by Colin M. MacKinnon

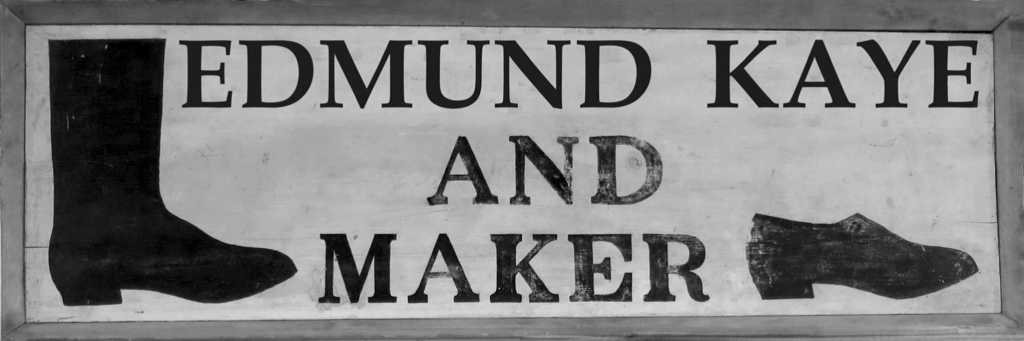

This past summer, while in Sussex, Nancy and I paid a visit to the Agriculture Museum of New Brunswick. One of the items that caught my eye was an interesting vintage sign that once advertised “M. L. Hines, Boot and Shoe maker”. Signs like this, showing symbols, were more common in the 19th century when literacy rates were lower and a business did all they could to attract clients. Using some “cut and paste” computer techniques, I altered my photo of the sign to suggest what “Edmund Kay”, a little-known Rockport entrepreneur, may have used (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Advertisement of the style that may have graced Edmund Kaye’s boot and shoe shop at Wilbur’s Cove, New Brunswick.

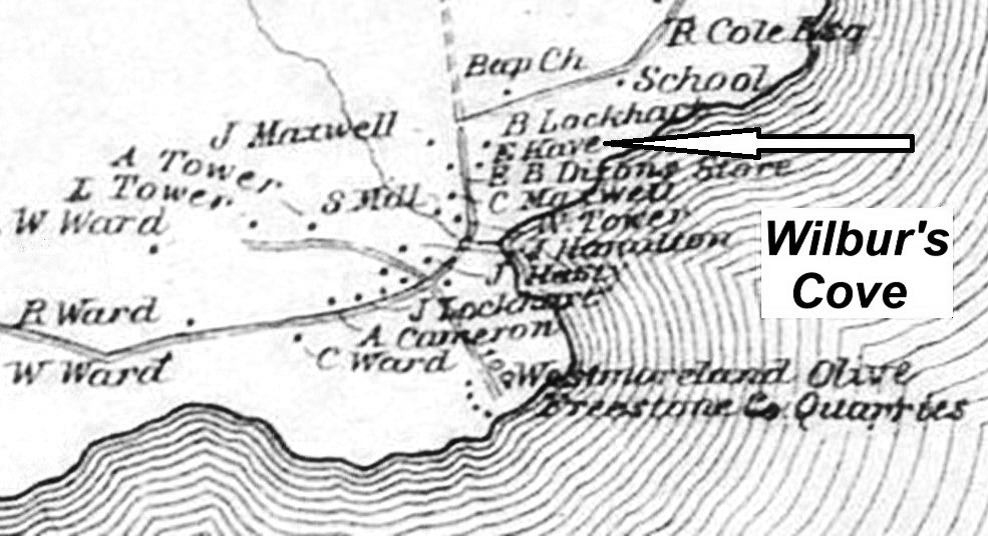

While perusing late 19th century census records for the Rockport area, I spotted a few “uncommon” names, or at least different from the more frequently encountered old peninsula names of Cole, Delesdernier, Maxwell, Lockhart, Tower and Ward. One such example was Edmund Kaye who, at age twenty-four, appeared there in the 1861 census. Also in the household at the time was his half-sister Nancy Hopkins (age 15). The location of his residence, and presumably cobbler’s workshop, is depicted on the so-called “Walling” map of 1862. The house was situated on a hill overlooking Wilbur’s Cove (Figure 2) with E.B. Dixon’s store across the road (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Situated overlooking Wilbur’s Cove, we believe the house in the foreground belonged to boot and shoe maker Edmund Kaye, later to be occupied by Alexander O’Brien Tower (1862-1933) and family. Photograph courtesy Silvia Ison collection.

Figure 3. Edmund Kaye’s residence (arrow) situated at Wilbur’s Cove, Rockport, New Brunswick (portion of the “Walling” map, 1862).

By the 1871 census, Edmund Kaye (age ~31) was listed as a “Shoe Maker” and a Baptist of Scotch descent. Oddly, however, within the household his half-sister Nancy is absent, being replaced by her younger sister, fifteen-year-old Melinda Hopkins (1855-1873) and a child Georgiana Murch (age 3). Both Nancy and Melinda were daughters of Walter Hopkins and Jane Kay of Westcock. On the 23rd May 1873, Edmund married Mary Jane Ward (circa 1842-1899), the widow of Rockport carpenter Daniel J. Ross (1832-1866). Mary was the daughter of grindstone-cutter (miner) William Ward and his wife Antrissa McFarland.

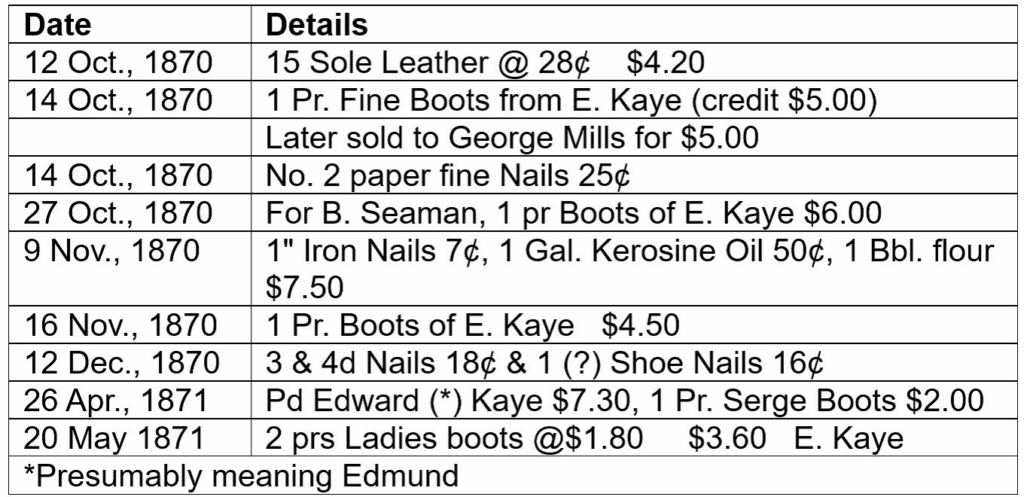

The importance of the Cape Maringouin peninsula to the stone trade is well documented but one of the more obscure sources about this industry is the store ledger books for Read, Stevenson & Co. They had an operation centered at Wilbur’s Cove from 1865 to the early 1870s. The original books are on file at the New Brunswick Archives in Fredericton (filed as: Read Stone Co. Ltd. MC224). Although they make rather dry reading, the documents are full of historical tidbits that can’t be found in any other place. The accounts record the day-to-day business of goods being bought, sold and exchanged as well as prices paid. Examples of a few brief entries regarding Edmund Kaye are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Select entries from the Read, Stevenson & Co. store ledger pertaining to Edmund Kaye’s Boot and Shoe business at Wilbur’s Cove. New Brunswick Archives. Read Stone Co. Ltd. MC224

Although the information is sparse, it appears that Kaye purchased at least some of his materials needed for making foot-ware, as well as selling the finished products, through the Read, Stevenson & Co. store. Considering that the working wage for a labourer in 1870 was about $1.00 per day, a pair of boots from Edmund would have represented a week’s salary. An interesting detail revealed from the ledgers was how frequently stone workers purchased boot nails and sole leather for their own use. With working days spent walking over abrasive sandstone rocks and ledges, they presumably developed the necessary skills to repair their own boots.

Sadly, some genealogy accounts suggest that boot and shoe maker Edmund Kaye died in 1873. Although possibly just a coincidence, it is said his half-sister Melinda Hopkins died that same year. If he did pass away in 1873, we don’t know where Edmund is buried. He could have been interred in the large Rockport cemetery or, being Baptist, may be in the little “Cole Memorial” cemetery situated just a few hundred meters up the hill from his house. The little girl, Georgiana Murch, mentioned earlier in this story, remains a mystery and it is quite possible that “Murch” is a misinterpretation of the name (a rather common occurrence when transcribing census records).

Announcements

Heritage Day 2025

Saturday, February 15, 2025, 2 p.m.

Council Chambers, Tantramar Town Hall, 31 Main St., Sackville, NB

Before the Quarry Park opens officially, learn about the history of this remarkable place from Paul Bogaard. Everyone is welcome. A reception with light refreshments will follow.

For more information, email tantramarheritage@gmail.com or call 506-536-2541.

Presented in partnership with the Municipality of Tantramar, Tantramar Outdoor Club, and Chignecto Naturalists’ Club.