march 2025

Editorial

Dear Friends,

Our home, the Isthmus of Chignecto, is highly vulnerable to flooding. The construction of flood mitigation ponds in Sackville over the past few years to collect floodwaters during severe storms is clear proof of this. In this issue of your newsletter, Al Smith documents historic floods in the area spanning a period of 158 years. He details for us five significant flooding events in the Tantramar area, including four press reports, dating between 1759 and 1972 (and a close call in October, 2015!). Al’s account is not only a review of past historic flooding events; it is also a warning. Read it carefully.

Over the years, your newsletter has often dealt with issues of navigation; this issue is no exception. In the previous century, Sackville had a seaport with a wharf on the Tantramar River at Dixon’s Landing (now buried in Fundy mud) and maintained important trade with cities along the eastern seaboard. Even navigating up the Tantramar River in the mid-nineteenth century had its hazards.

Colin MacKinnon has uncovered reports in newspaper accounts of sailing disasters on the Tantramar River between, and including, the years 1876 and 1902. These stories and dramatic reports of the dangers of seafaring life inform us of the risks that were involved when one chose a life at sea and the important role oceanic trade played in Sackville’s history. After all, we have a museum in Sackville (the Boultenhouse Heritage Museum) dedicated to shipbuilder Christopher Boultenhouse whose father and son Charles were both sea captains.

To complete this issue, Al Smith takes us back to “What’s in a Name,” a feature column we carried in earlier issues of this newsletter, and explores the origins of the name Landing Road, which led to the Port of Sackville (yes, you read correctly!). Read on and discover more of the interesting past of life at sea and on the Isthmus of Chignecto.

Enjoy!

—Peter Hicklin

The Fundy Storm of October 1, 1917

by Al Smith

Greatests Tides Since the Famous Saxby – Marsh Between Sackville and Aulac Like a Sea: All ICR Traffic Hung Up on Account of Bad Break in Roadbed: Men Work All Night.

October 1, 1917 flood on the Tantramar showing 80-100 men repairing the railway. Al Smith’s postcard collection

So read the headline of a major news article in the Tuesday, October 2, 1917 edition of The Chignecto Post newspaper. Many years ago my neighbor Marg Stevenson gave me an old postcard that she had discovered in her historical house (the “Bell House”, currently 245 Main Street). That postcard was a photo of a flood on the Tantramar Marshes showing railway crews repairing the washed out rail bed. The postcard was not dated, but with the help of Donna Sullivan in the Mount Allison Archives, it was soon determined to be a photo taken of the damage caused by a severe Fundy storm on October 1, 1917. So with the recent high interest in shoring up the dykes in the Chignecto Isthmus I thought it was timely to research this major storm of 108 years ago.

Historically, there have been a number of storm tides that have caused severe damage to coastal communities and infrastructure around the Bay of Fundy. The low coastal marshes at the head of the Bay were especially vulnerable to Fundy storm tides. The first recorded severe storm, a combination of windstorm and high tides, was on November 3-4, 1759. That storm broke down dykes throughout the Bay of Fundy and at Fort Cumberland (Beauséjour) on the Tantramar Marshes; 700 cords of firewood were swept out to sea from a wood storage area that was at least 10 feet higher in elevation than the tops of the dykes.1 That storm tide was estimated to have been six feet (1.8 meters) higher than normal.2 As a result of that storm, when the first New England Planters arrived in 1760-61 they found broken Acadian dykes, damaged aboiteaux and dykelands flooded with salt water.3

Possibly the most famous and destructive Fundy Storm was the Saxby Tide (better known as the Saxby Gale) of October 4-5, 1869. Much has been written about this major storm that broke dykes and flooded the entire marsh regions at the head of the Bay. On the occasion of the 150th Anniversary of that major event, the Tantramar Heritage Trust held its annual “Taste of History” dinner in September 2019 with a Saxby Gale theme, including an original play. That severe storm overtopped dykes, breaching them in numerous locations, drowned cattle and sheep and washed away portions of the newly-established railroad bed. Two fishing schooners were lifted over the dykes of the Tantramar marshes and deposited five kilometers inland.4

More recently, the Groundhog Day storm of February 2, 1976, with gale force winds and a deep low pressure system, caused significant damage along the coast of Maine where tides rose more than 2.5 meters (8 feet) above predicted levels for that date. Fortunately, the storm occurred at a time of lower monthly tides (neap tides). If it had occurred during a spring tide (full or new moon) the amount of damage would have possibly rivaled that of the Saxby Gale.5 Here in the Tantramar it was mostly a very severe wind event.

So let’s go back to the storm of October 1, 1917. Curiously there has been very little written about this significant Fundy storm. Desplanque and Mossman in their published Storm Tides of the Fundy6 do not mention it. Fortunately, both Sackville and Amherst newspapers recorded details of the storm and we have a local photograph record. The Sackville Tribune edition of October 4, 1917 reported the following.7

Turbulent Tides Break Dykes and Do Great Damage

The Loss Will Amount to Many Thousands of DollarsBeginning last Monday [October 1], at about noon, exceptionally high tides prevailed around the shores of the Bay of Fundy and its tributaries. So very high did the tides rise that the famous Saxby tide of many years ago was forcibly recalled. Very great damage, the extent of which is very difficult to estimate, has resulted.

Thousands of acres of dyked land has been inundated, thousands of tons of hay have been destroyed, considerable damage has been done to the roadbed of the Canadian government railways, and altogether the ravaging of the tide have proved most serious.

Reports from Albert County, Minudie, Amherst Point and other places drained by a tidal river or estuary flowing into the Bay of Fundy, state that the damage has been very great and will prove a very serious loss to hundreds of farmers who can ill afford this burden at this season of the year. Perhaps the most serious aspect of the case lies in the scarcity of labor necessary to repair the broken dykes. Great ragged gaps have been torn in the big dykes and it will take many hundreds of men many weeks to repair the damage. The extreme scarcity of men who know how to dyke makes the task which confronts the marsh owners one of the most serious which they have been called upon to face for many years.

The first high tide was Monday about noon. The dyked lands which stretch to the east and south of Sackville were soon a surging sea. Trains were held up in Sackville, Amherst and Moncton and other points and much inconvenience was suffered by many passengers who, for one reason or another, were eager to proceed on their way. For more than twelve hours no trains passed through Sackville. The washout for nearly a mile immediately west of Aulac was of the most serious character. The road was completely washed away and left the rails attached to the sleepers suspended at various angles and in very bad shape. Hundreds of men were immediately placed on the job and work on repairing the damage begun. One tide subsided and then another came doing still more damage, still the work on repairs went on, when possible. At length the tides eased away and did not rise so high. Yesterday [October 3] the trains went very slowly over the damaged railway and it is expected within the next few days everything will be operating as usual.

The future looks rather dark, however, inasmuch as another very high tide is predicted in three weeks time. The dykes can not be repaired within that time so a repetition of inundated marshes and damaged roadbed may be expected. There have been various reports of horses and cattle being drowned in the flood but, as far as The Tribune knows, there is no truth in such. During the highest tide, the main highway between Sackville and Aulac was covered with three feet of water and presented a very strange sight. Many people viewed the floods from various points of vantage and marveled over the turbulent torrents surging over the low-lying lands. The very high winds on Monday made the tide higher than it otherwise would have been.8

View towards Aulac – notice the washed out sides of the railway. Mount Allison Archives, Anderson family fonds 8317/10/8

Sackville’s second newspaper The Chignecto Post was also published twice weekly on Tuesdays and Fridays so they had the first chance to report on the storm. The Post’s issue of Tuesday, October 2, 19179, reported extensively on the flood. “At noon yesterday it would probably have been possible to make the trip between Sackville and Amherst by boat” as the roads between the two towns were flooded to a considerable depth and even the road to Sackville’s Public Landing had a foot or more of water covering it. They also reported that many rail passengers were arriving at the Sackville ICR station and practically every automobile in town was engaged transporting them from Sackville to Middle Sackville and across the marsh (i.e. across the High Marsh Road) to Pt. de Bute and on to Amherst. Despite the efforts of one hundred men working around the clock repairing the railway, traffic moving south did not resume until Tuesday evening or Wednesday. The railway from Sackville to Moncton remained open; however, the marshes between Dorchester and Memramcook were also badly flooded.

The Chignecto Post also reported that “stacks of hay have been torn from their foundations and a quantity of late hay has been submerged. At least in a few cases, potatoes and grain have been covered with water and it has been reported that a number of marsh barns have been flooded off their foundations”. There were also reports of drowned cattle but the newspaper was unable to verify that.

The Chignecto Post issue of Friday, October 5, 1917, had a follow-up article that contained quotes from an Amherst News reporter who visited the site the day after the Fundy storm tide:

“Standing on the track this morning [October 2] at Aulac nothing could be seen on the seaward side, but a wide expanse of rising water. Dykes were covered with the flood. Stacked hay floated over the marshes in vast quantities. An hour or so before high water the tumultuous sound of in-pouring tide through the broken barrier [dyke] forbade speech. The westerly wind yesterday caused all the damage. The waves rolling in [had] gouged out the gravel from between the railway ties in great masses, and hurled the debris thirty and forty feet on the leeward side of the track. Twenty minutes of high tide and the railway was made impassable.

“Talking to an old railway man this morning, the newsman was informed that nothing like it had ever been seen before in this section of the country. Of course the Saxby Gale was infinitely worse but the high tides on a Sunday, seventeen years ago, [1900] failed to do half the destruction. The railroad business then was only tied up for a few hours.”10

Local marsh owners gathered in Dixon’s Hall in Sackville [Amasa Dixon building on the corner of Main and York Streets] on the evening of October 9, 1917, to consider the question of repairing the dykes and aboiteaux. The meeting was chaired by Albert Anderson. Work had already begun repairing the dykes and it was hoped that it could be completed before the next period of high tides. The Canadian Government Railways had offered to contribute $500 towards those repairs and it was expected that the Province would also help with the costs.11

So, including the year 1900 flood, referenced above, there have been at least four occasions when the seawall dykes have been overtopped by Fundy storm tides. Granted the present seawall dykes are much higher than those dykes that existed during the Fundy storms mentioned above, but so is sea level rise. According to Desplanque and Mossman sea level has risen more than 25 centimeters (circa 10 inches) between the Saxby Gale of 1869 and 1999 when they published their paper on Storm Tides of Fundy.12

So by using their calculations of an increase of 2 mm/year of sea level in the Bay of Fundy is, today, approximately 30 cm higher than it was in 1869. Add to that the increased intensity of storms, especially tropical storms with very high wind velocities. Should such a deep low- pressure system (like a hurricane or tropical depression) coincide with a period of high monthly tides, then the potential for dyke damage and flooding is much higher.

Tantramar flood October 1, 1917. Mount Allison Archives. Donald F. Taylor fonds 7601/2/125

Southeast view from the railway wit Cole’s Island in the background. The main road between Sackville and Aulac is completely submerged. Donald F. Taylor fonds, 7601/2/125

On October 29, 2015, the Fundy tides nearly overtopped the dykes.13 The Canadian National Railway line between the Tantramar River Bridge and the Aulac River is the “dyke” that protects the main Tantramar Marsh from tidal flooding. Tidal waters in recent years have come perilously close to lapping the rails. Historical storm tides have caused major damage in the past and as Desplanque and Mossman concluded in their 1999 article:

“With continuing global sea level rise and regional crustal subsidence, the possible recurrence of destructive storm tides has grave implications for property owners and settlements in the Fundy coastal zone.”14

Endnotes

1. Desplanque, Con and Mossman, David; Storm Tides of the Fundy, Geographical Review, Vol.89, No. 1, January, 1999, pp 23-33.

2. Ibid.

3. Milligan, D.C., Maritime Dykelands — The 350 Year Struggle, 1987, page 5, ISBN 0-88871-085-2

4. Desplanque, Con and Mossman, David; Storm Tides of the Fundy, Geographical Review, Vol.89, No. 1, January, 1999, pp 23-33.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. The Sackville Tribune newspaper back in 1917 published two issues weekly, on Mondays and Thursdays, so even though the storm occurred on Monday, October 1, they did not get a chance to report on it until their next issue on Thursday that week.

8. The Sackville Tribune, Thursday, October 4, 1917, Mount Allison Microfilm Library—Micro 5227.

9. The Chignecto Post, Tuesday, October 2, 1917, Mount Allison Microfilm Library—Micro 5454.

10. Ibid.

11. The Sackville Tribune, Thursday, October 11, 1917.

12. Desplanque, Con and Mossman, David; Storm Tides of the Fundy, Geographical Review, Vol.89, No. 1, January, 1999, pp 23-33.

13. Jeff Ollerhead lecture to Tantramar Seniors’ College, February 13, 2023.

14. Desplanque, Con and Mossman, David; Storm Tides of the Fundy, Geographical Review, Vol.89, No. 1, January, 1999, pp 23-33.

A Treacherous Passage

Navigating the Tantramar River to the Port of Sackville during the Age of Sail

by Colin M. MacKinnon

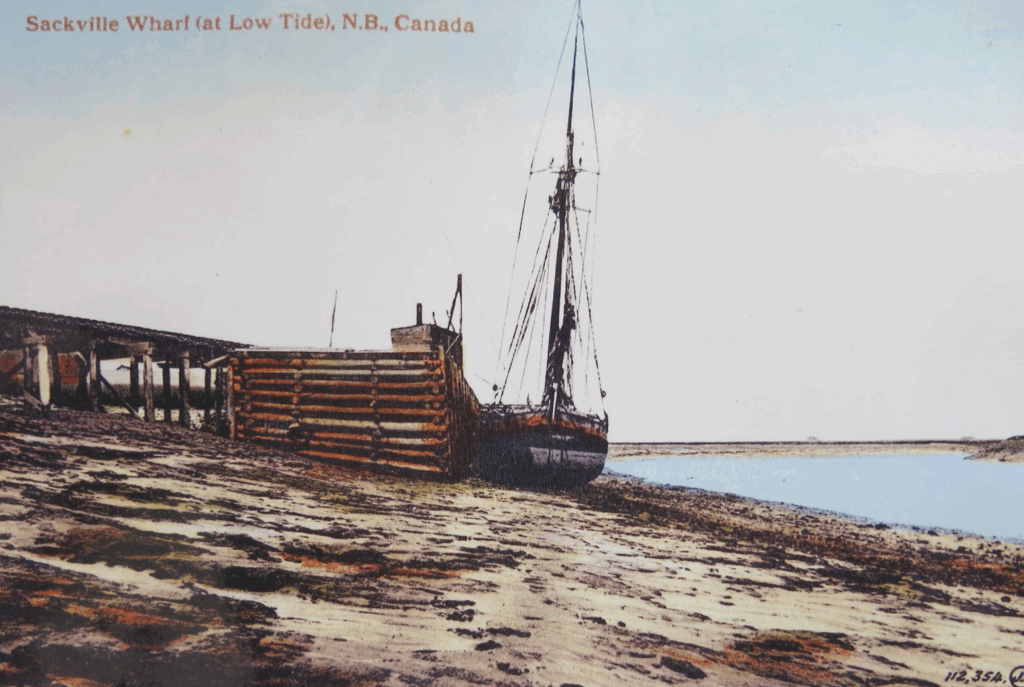

During Sackville’s “heydays” in the age of sail, not only did we have a thriving shipbuilding industry but also a busy seaport. Newspapers throughout the later half of the 19th century frequently posted columns under the titles “Shipping News” or “Marine Intelligence” where the whereabouts of local ships and captains were noted either entering or leaving ports-of-call or having been “spoke” (seen by another ship) at sea. Some of these news articles also mentioned marine accidents: vessels lost or close calls. The following excerpts mention a few such incidents at the Port of Sackville (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A small schooner tied up at the Sackville wharf at low tide.

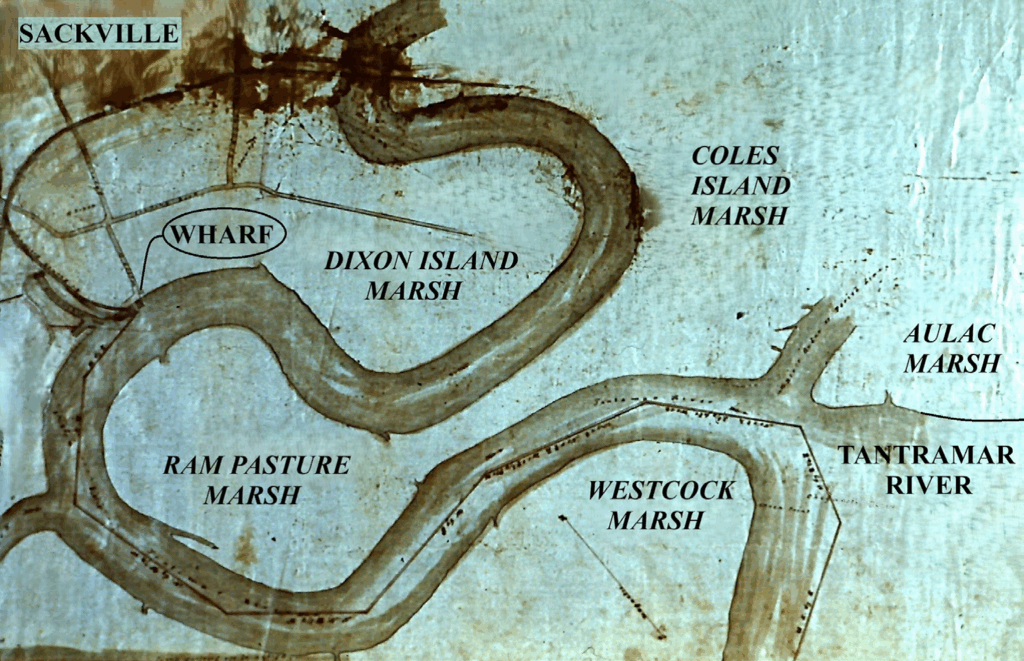

But first, some background. The approach to the “old” Sackville wharf, built at Dixon’s Landing in 1840- 1841, consisted of navigating six kilometers of the narrow and circuitous Tantramar River. At high tide, this waterway was about 500m at its mouth; however, as one followed the river upstream, this width gradually diminished to only about 200m at the dock (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Navigation chart for the Tantramar River and the Port of Sackville. Courtesy of Phyllis Stopps.

I assume that most sailing vessels ascended the river on a rising tide and departed on the ebb. Thus, navigating the river, with such a narrow margin for error, must have tested the skills of the ship captains and crew. By the early part of the 20th century the course of the Tantramar river was to change. Our pre-1900 maps of the area show a large oxbow in the river, as described above, it encircled most of the 250 acre (100 ha.) Ram Pasture Marsh. The “Ram Pasture” would have been an island except for a narrow neck of land that connected it to the adjacent Coles Island Marsh. This is the situation that the mariners encountered in the following accounts, but it’s not what we see today (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Present course of the Tantramar River by-passing the old Sackville wharf. Google Earth 2024

By the late 1800s, this neck of land was getting narrower due to erosion, such that the course of the river was changing. Over time, the volume of water that flowed around the Ram Pasture and past the old Sackville wharf was decreasing. By the 1920s, the main river ceased to follow its old route around the oxbow as the old bed of the Tantramar was being steadily infilled with tidal silt.

The so-called “new wharf”, completed in 1911 and situated 500m downstream of the old wharf, was built at a precarious time when these changes were taking place. One can visit the “new wharf” today, although the majority of the structure is now entombed in marsh mud (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Top: Sackville’s so-called “new wharf” completed in 1911. Archives of Public Works Canada.

Bottom: View of the same wharf site today. The old river bed has been filled with silt with only the tops of the dock’s bollards sticking out of the saltmarsh.

At the time these changes were happening, local merchants complained about the loss of shipping and the infilling of the river by the wharf. However, prominent farmers saw an opportunity to rejuvenate more dykelands through a process called “warping” or “tiding” as the now shortened length of the river would allow a greater load of “rejuvenating” tidal silt to be flushed up the river on each rising tide.

In 1896, an eyewitness to these events was dykeland authority George J. Trueman, who made the following observation:

“North-east of Cole’s Island the Tantramar curves out, then doubles back on itself, leaving a point of land joined to the mainland by a narrow neck sixty feet wide. High tides swept over this and rendered the point unfit for cultivation. The water going up the river kept its old bed, but no sooner would it get around to the upper side of the neck than it would rush back over the neck to return again by way of the main river. This gives one an idea of the rapidity with which the water rises as it runs up the river. This neck was cut off in 1893 by two of Sackville’s enterprising farmers and in 1894 there was twenty feet of mud deposited in the old channel. Several acres of marsh will be made from the reclaimed point and the old river bed. If a canal were cut through the Ram-pasture neck, a similar curve further down, a much larger piece of marsh would be given to the country. Unfortunately, the wharves are situated on the curve, and such a change would necessitate their being moved to another part of the river. So great is the rush of water back over this neck when the tide is flowing in, that several hundreds of dollars have been spent by the government to prevent the neck from wearing out of itself.” (The Marsh and Lake Region at the head of Chignecto Bay, 1899, p. 100).

The following four accounts provide a glimpse of the perils in navigating the Tantramar River and negotiating the wharf. The first article, from 1876, actually pertains to the loss of cargo by my great great grandfather, Capt. Seth Mark Campbell (1818-1880) and the brig “Magdala” (Registry No. 59,175). The second piece is about the 160-ton schooner “Ella Maud”, commanded by Captain Patterson. The “Ella Maud” (Registry No. 80,867), was built at “Joggins Mines” in 1885. By 1890, the vessel was owned by Frederick W. Sumner of Moncton. I am uncertain as to the identity of Captain Patterson but he may have been from nearby River Hebert or Shulie. The third story tells about the barque “Siddartha”, under Capt. C. Moore and a harrowing event while crossing the Atlantic only to reach port and get fouled up with the barque “Daisy” on the Tantramar River. The “Siddartha” (Registry No. 77,894) was a large ship (463 Net tons), built in Sackville by Edward Wood Ogden in 1880 and owned by E.W. & A. & W. Ogden and later by Josiah Wood. It measured 146.5 x 32.5 x 12.9 Ft. and carried the International Code Signal “T.W.R.S.”. The log book for this vessel, from 1893 to 1895, is part of the “Webster Manuscript Collection” held by the Mount Allison University Archives. The final story concerns Capt. Fred W. Cole, his mate Mr. Sterling, their swimming skills, and a close encounter with a near watery grave. The four news articles follow.

Brig “Magdalia” [Magdala,],

9 June 1876—“Capt. Seth Campbell, loaded at Sackville with hay, oats and spars for the West Indies. Got ashore in Sackville River [Tantramar River] and filled with water, damaging the cargo which has to be discharged. This happened the 6th inst.” (Diary of Gilbert Seaman, 1875-1885, edited by Susan Hill).

Schooner “Ella Maud”, 1885—

“Capt. Patterson, master of the schooner “Ella Maud”, is having an unpleasant experience in our port. When he arrived here Monday morning, the berth at the end of one of the wharves was occupied by the barque “Eyr” and, as there was no harbor master to attend to such matters, the berth at the other wharf—the only one available for a loaded vessel—was taken by a wood boat, which arrived a few minutes before the “Ella Maud”. The only course remaining for Capt. Patterson was to lay his vessel with a cargo of 234 tons of coal and 494 barrels of oil outside of the wood boat, where he would be able to discharge except at a great disadvantage. The master of the wood boat on learning the state of affairs was willing to be accommodating, and give up his berth, but when he got ready to draw out from the wharf he found that his vessel had taken the bottom, and could not be moved. When the wood boat floated again she was hauled out, but the tide had neaped in the meantime, and the “Ella Maud” was unable to get to the wharf. When the tide ebbed she listed off from the wharf and filled, while her deck load of oil went overboard and floated away. The vessel which is nearly new—this being her third voyage—is considerably damaged, and will have to be partly discharged before she can be floated, and the work of discharging, owing to her position, will be attended with great difficulty. Capt. Patterson speaks gratefully of the kindness of the people who went to his assistance and did all they could to aid him, but, as a matter of course he is not very favorably impressed with the sagacity and enterprise of the merchants and ship-owners of Sackville who allow a port like this to be without a harbor master and without sufficient wharf accommodation. There certainly seems to be grounds for believing that those most deeply concerned are pursing a very foolish course in this matter, and one that can scarcely fail to be injurious to both public and private interests. Capt. Patterson has formed a favorable opinion of our river, and says that although he has had considerable experience in the navigation of the principal rivers of our coasts, he never had less difficulty in getting into any of them than he had in sailing up the Tantramar. But natural advantages will be of no avail unless suitable provisions be made for the safety and accommodation of vessels that come to our wharves, and if the present short-sighted policy be continued there will undoubtedly be an ever-increasing difficulty in persuading ship-masters to visit our port. The “Ella Maud” was surveyed yesterday by Captain Chas. Moore, Wm. Pringle and Ed. Ogden. They report she has received serious damage by straining. Her butts are started, covering board streak opened and the tide flows in and out of her. She is insured for $4,000 in St. John agencies. She is to be discharged into a wood boat as she lies, after which a second survey will be held.” (Chignecto Post, 15 October 1885)

Barque (bark) “Siddartha”, 1888—

Report of the bark Siddartha, Moore, from Liverpool to Sackville.—Sailed Aug 19th, and had calms and head winds in the Channel for one week. Had moderate weather and westerly winds up to the 12th Sept, when we experienced a heavy gale from the north accompanied with terrific squalls and high sea, shipped considerable water about decks, etc. On the 19th Sept, went through a gale of hurricane force from south and shifting north, in which we lost lower fore topsail. Ship was hove to 12 hours and labored heavily, shipping seas and washing battens off hatches, etc. 20th, we passed bark Privateer, of St. John, from Liverpool to New York, with loss of canvas. Same day passed another bark with nothing set but a storm spanker. Weather fine. Thence into port had fine weather. Spoke German ship Wilhelm, from Bremen to New York, on the 8th, 21 days out.” (Chignecto Post, 2 October 1888)

“Shipping Items—On Monday morning a collision occurred in the river between barque “Siddartha,” Moore master, and barque “Daisy,” Lewis master, both bound up. The “Daisy” had her fore top gallant mast and jib-boom carried away.” (Chignecto Post, 2 October 1888)

Schooner “Mabel”, 1902—

“A Narrow Escape: Capt. Fred W. Cole had a narrow escape from drowning on Sunday morning. He was navigating the schooner “Mabel” up-the-river when in consequence of the high wind, she touched on the bank. In order to get her off the Capt. and mate Sterling put off in a boat with a cage anchor. In throwing the anchor the rope in some way got caught around the Captain’s ankle. He called to Sterling to cut the rope but in trying to do so, the boat filled and sank and Capt. Cole with the rope around his ankle was carried to the bottom whence with considerable difficulty he managed to free himself and rise to the surface. Both men succeeded in reaching the schooner but had they not been particularly good swimmers, they would certainly have drowned.” (Chignecto Post, 21 August 1902)

What’s in a Name?

Landing Road

Landing Road, a short, dead-end roadway off Crescent Street, was once a busy access to Sackville’s public landing, where wharves, and at one time a shipyard were located. The road was likely built around 1840 and was located on a narrow finger of upland that reached out to the edge of the Tantramar River channel, at a site that was once known as Dixon’s Landing. At this site local merchants began developing a Public Wharf at the edge of the river in 1840. Completed the following year, this first public wharf greatly expanded capabilities for importing and exporting of goods. In 1849 Charles Dixon and his business partner Mariner Wood established a shipyard at the mouth of Bowser’s Brook, just north of the public wharf. Charles Dixon built eight vessels at that shipyard including the 1468-ton ship Sarah Dixon. Launched in September 1865 it was the largest vessel built in Sackville area shipyards. The Dixon shipyard site was later used by Capt. George Anderson and Edward Wood Ogden for construction of vessels.

The original 1841 Public Wharf was small with just a 50-foot frontage on the river so local merchants Amos & William Ogden along with Mariner Wood constructed the private Wood/Ogden Wharf just downstream from the Public Wharf. In 1877 that wharf was connected by a spur line to the main ICR line. With the completion of the NB & PEI railway in 1888 a second spur line was added along with a new section of wharf, known as the Railway Wharf, which greatly added dockage space for vessels entering the port. With the addition of the Railway Wharf combined with the older Wood/ Ogden Wharf still only gave a frontage of about 232 feet to conveniently accommodate one vessel at a time. Sackville was a busy seaport with 60-80 vessels entering and leaving annually. Shipping traffic continued steadily as in 1904-1905 70 vessels arrived but by 1909 it had declined to 45 vessels offloading 5000 tons of cargo.

The 1899 map of Sackville published by Stewart & Co. names the road Water Street. Following the Incorporation of the Town in 1903, the Town Council Streets Committee recommended the name Water Street “from Crescent Street to the Public Wharf”. That name may have been used for a couple of decades but the circa 1920 river breach and rerouting of the main channel of the Tantramar River resulted in the destruction of the port due to infilling by tidal silt. The road no longer went to the water but still went to the site of Dixon’s Landing. The name Landing Road was adopted and first appeared on the 1968 map of Sackville.

Town Council started looking at the old wharf site in 1933 for a Town Dump. It was established there sometime in the 1930s and remained there until 1977 when it was moved to a former gravel pit at Mount View.

Source: Smith, Allan D., Aboushagan to Zwicker—An Historical Guide to Sackville NB Street Nomenclature. Publication of the Tantramar Heritage Trust (2004).

Department of Public Works Canada; Report and plan from District Engineer Stead, February 23, 1912, National Archives of Canada, File 16258, document # 8932

Landing Road. Model of the Sackville wharves c1887 when they were active at the end of Landing Road. Model made by Peter Manchester and located at the Boultenhouse Heritage Centre, Parlour (Marine) Room, Sackville, NB.

Announcements

Annual General Meeting

Saturday, May 24, 2025, 2 p.m.

Campbell Carriage Factory Museum

Guest speakers: Dr. Cora Woolsey, Dr. Leslie Shumka, and John Somogyi-Cszimazia “The Boultenhouse Shipyard Archaeological Project”

Join us for a short business meeting, presentation of the Volunteer of the Year Award, and a presentation from our guest speakers. Reception to follow. All are welcome.

————

2025 Memberships

Have you renewed your membership for this year?

It’s only $20 for an individual and $30 for a family or institution and means you won’t miss an issue of The White Fence.

Contact Karen at 506-536-2541 or tantramarheritage@gmail.com to check your status.

————

The White Fence Compendiums

Did you know we’ve published three compendiums of our newsletter, with 30 issues of The White Fence in each? They’re a great way to keep your newsletters nice and organized, easy to pick up and browse the many great articles on local history.

Ranging in price from $20 to $25, they make a great gift.

Available at the Boultenhouse Heritage Centre and Tidewater Books in Sackville.